Photo by Jen Goellnitz

At age 69, my running these days consists mostly of alternating short bursts of slow running with short walks. If I’m rested and have my feet to the fire, I can run six miles or so continuously, but I rarely try. Despite this, my endurance is still good.

Personal circumstances led me to decide to sign up for the new 12-hour option at the NorthCoast Endurance Run in Cleveland this year (September 22, 2012), even though I did the 24-hour the first three years of the race’s existence.

Getting Ready

In the course of month in and month out training, I usually manage to get something just below 200 miles per month, with two or three months in a year over 200. In August I recorded 228 miles—not a bad month for someone rapidly becoming an old coot, given that I’m still working close to full time.

When it came time to bear down on what training I’d planned for the NorthCoast race, I decided that time on my feet, which is what I’m good at, would be the thing I’d emphasize. I planned 7-hour, 8-hour, and 9-hour loop runs three weeks apart, with the last on September 1, exactly three weeks before the race.

The place I go these days to do this sort of training is a bike path in a fairly isolated park called Sycamore Field in Columbus. The loop measures 0.78 miles on Google Maps (click the link to see it), and surrounds a large, open field big enough for several soccer fields, with lots of room to spare. It’s flat enough that it’s hard to decide if one direction is better than the other, although I always run clockwise, the direction NorthCoast is run. During a weekday afternoon, the typical density of foot and bicycle traffic there is to encounter one or two other people in three or four laps. In other words, it’s close to abandoned, even though it’s very well maintained, has two large parking lots, and a dog run that does get used just 100 yards to the north, and always has a regularly serviced porta-potty from spring until sometime in November. Two weeks ago I arrived on a Saturday morning to find they were using the field for a high school cross-country meet, allowing me to enjoy watching hundreds of fit, high-achieving teenagers run their hearts out as I circled the path while doing a final 10-miler in preparation for the race.

In each of my three fixed-time workouts, I was 100 percent successful in not stopping for anything whatever the entire time except for one potty stop per workout, and to grab water off the chair I’d set up. I was tired after each one, but I’m certain I couldn’t have lasted nine hours the day of the first one, so I must have made progress. And I do believe the effort paid off at the race.

Before the Race

Edgewater Park, on the shore of Lake Erie in Cleveland, where NorthCoast is run, is a drive of about about 150 miles, two hours and forty minutes one way from my home in Columbus, Ohio. This year I drove in on race morning, leaving a little after 5:00 a.m., arriving at precisely 7:40 a.m.

My gear plan was simple. For a 12-hour I could have survived entirely on what I wore on my back and not bothered with a personal aid station at all. But I learned there might be weather problems, so I packed some extra gear in a gym bag, including a four-pack of Red Bulls, which I hate, but buy and drink only when I’m doing a long run, sometimes drinking a can that’s been sitting in the hot sun for a couple of hours. I drink it for the jolt, not for refreshment.

All this stuff I set up on a folding camp chair. Total setup time: less than a minute after picking my spot, after which I checked out the nearest porta-potty (for the first time they had two near the start and finish area), taking care of some very important pre-race business in there, and then took off to find old acquaintances and make new ones, always one of my favorite rituals of any ultra.

Once a race starts I’m almost always a loner because (a) almost everybody goes faster than me anyhow; (b) I just do better when I concentrate on trying to work out my own salvation, though this race would prove to be an exception.

Along with all the rest, I had the pleasure of meeting John Hnat, the new race director, whom I’d talked to previously only in e-mail and on Facebook, and was impressed by what an upbeat and good-humored guy he is—qualities he would need about six hours later.

The Race

For a number of ingeniously thought-out reasons that added up to what seemed like a good idea to me, they moved the start back around the bend this year, about a tenth of a mile. That extra distance was added to everyone’s totals at the end.

The weather at the start was cool but comfy, super for running, and there were partly cloudy skies. Sometimes the sun peeked out, and it got almost warm. After a few laps I took off my red jacket and tossed it on my chair, leaving me wearing only shorts, a short-sleeve running shirt (last year’s race shirt) and a super-lightweight long-sleeve running shirt over it. Well—and a hat and shoes and big, fancy underpants, of course.

One woman, Hannah Critchfield, ran barefoot, and was running well—not a leader, but steady all the way. I never saw her walking. She stuck it out, and finished the 24-hour race with 79.3 miles, a fine performance. I remember a barefoot runner winning Tucson Marathon two or three years in a row, though I didn’t get to see him because I was on the other end of the race, of course. Most of Tucson Marathon is run on the rocky shoulder of a highway. Don’t try that yourself, folks. I don’t know how anyone does that. Just gimme shoes!

Historically, I’ve had some of my best outings in 12-hour races. Most of the eight or so that I’ve run have been very low-key semi-official but accurately timed and measured and well-supported races, including one all-nighter at Nardini Manor in Arizona (former home of Across the Years) one summer where there were only three of us at the starting line, though numerous others joined in later. And we were also the last three out there, all of us running until the end. I was the slowest of the three, but I got the “bronze”—I had the third most mileage of all participants by about twelve miles.

My goal at North Coast this time was modest: 40 miles, but a bit of a challenge, because I haven’t gone that long in a while, and I’m not running like I used to. Yet it was sufficiently doable that I thought if I didn’t make it, it would be a big disappointment. My secondary goal was to avoid stopping for anything other than a potty stop and to grab water or food.

So we were off at 9:00 a.m. The first thing I noticed was the timing system rocked, seemingly state of the art. Having been involved with races of this type on the creative end myself for quite a number of years, I know that timing is the single most difficult problem to get right, and just about the most important, along with providing a good course to run on. At the spring edition of NorthCoast last May, which was the USATF national 24-hour championship, there were horrendous problems with the timing. It basically didn’t work. Although they eventually got it mostly straightened out, a consequence of the misstep was that a runner ran what was potentially a new US women’s record for 24 hours, but her performance was unable to be validated and ratified. Such a happening, particularly at a national championship, is a crying shame, especially for the runner affected. After all, record performances don’t grow on trees.

The bottom line is that sort of thing simply mustn’t happen. It can, but every reasonable effort must be made to assure that it won’t. Prior to this race, John Hnat sent e-mail to participants explaining the new system that they would be using. Most important in any fixed-time timing system is not the glitzy (but thoroughly enjoyable) external features: multiple highly visible computer displays showing everyone where they’re at and the like, which are now becoming de rigueur at the best races. Far more important is the backup method used to assure that the end results will be correct in the event of failure, which can and does happen if there is a total power or main computer failure. I don’t remember the details of what John related, but it was sufficient to give me the warm-n-fuzzy necessary to be confident things would go well—as indeed they did, even though later happenings would prove to put the system to the test.

And for the first six hours I had one of the best runs I’ve had in years. Not only did I become certain that I would make my goal; I also anticipated exceeding it by perhaps as much as five miles if I could just hold steady, and given how well and under control I felt, I had every reason to believe I would.

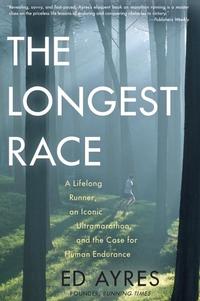

Something that helped me greatly was a new book about ultrarunning I’d been reading for a couple of days prior to the race. The book is by Ed Ayers (a runner and ultrarunner for 55 years and founder of Running Times, for those who don’t know him). Ed’s new book, not yet published (it’s due out in October 2012), is titled The Longest Run. As a fellow editor, the author had his publisher send me a pre-publication “uncorrected” copy for review. I’ll be writing a summary of it on my blog and will have a word or two to share on the lists very soon. (I finished reading it this morning.)

In the course of reading The Longest Run, I made a few notes for what I’d have to say later, and in the process picked up some pointers and was also able to review some fundamentals. Review is good. As a lifelong student of many subjects and a sometime teacher and writer, I’ve learned that it’s often good to go back to page one on any subject and review the basics, in the spirit of what the apostle Paul wrote about understanding Christianity:

If anyone thinks he has acquired knowledge of something, he does not yet know [it] just as he ought to know [it].—1 Corinthians 8:2

In a sense, review is like a musician running down scales and arpeggios. It’s not that he doesn’t know them; it’s that he could know them a little better, and these fundamental exercises will help him play real music better because he’ll be less preoccupied by technical obstacles.

And so it was at Edgewater Park on Saturday that rather than allowing my mind to spin off dissociatively into thinking about whatever came to mind, instead I concentrated on thinking associatively about what I was doing, paying closer attention than I have for a long time, because after all—this was it—I was in a race, trying to do my best, and I don’t know how many more of these things I’ll be able to do.

My attention-paying actually began the night before with the pre-race meal I ate. Carboloading on pasta, which I learned about when I first took up racing, may still be popular in some quarters, but I believe it’s waning in popularity, as experienced runners now realize that for a lot of reasons, pigging out before a race isn’t such a good idea. I limited my pre-race dinner to a medium size baked potato with bleu cheese and a veggie burger on top of it. (No, I’m not a vegetarian, but don’t eat meat daily.)

The second matter for attention was eating during the race. Another popular myth is that a runner needs to eat several times his usual rate of calorie consumption during a race, chowing down food every couple of miles. Experienced and efficient runners will tell you this is not true. Rather than set some sort of arbitrary pattern, the best policy is to listen to one’s own body. Most runners should be able to survive at least a 50 km race on little or nothing more than they would eat normally during that time span. Past a few hours, of course, runners will need to eat a combination of standard nutrients, including some fats.

Every 24-hour race I’ve been at the last few years I’ve been amused at the setups some runners who come with crews have. I’ve seen tents that look like outposts of GNC health food stores, with racks of shelves filled with powders and gels that come in large, plastic bottles and cans, and with names that end in -yte and -ox. I have to wonder if the runners they support would do better if they ate actual food.

The food offered at most races is mostly unappetizing to me. I can’t imagine trying to eat a quarter of a peanut butter and jelly sandwich that has been sitting out exposed to the air and drying up for hours, and has been visited by who knows how many flies, nor will I take a chance any longer on food that is grabbed out of a dish that many other sweaty people who have been stopping at porta-potties have grubbed around in before.

I’m prone to eating cookies and candy and pretzels when I really shouldn’t, but not so much during races, when they might be just what I need. Sometimes I can handle M&Ms. About two hours into the race I indulged in a single Oreo cookie. I was still chewing and gagging on it when I came around on the next lap. And yes, I was keeping up rather well with my hydration, drinking mostly water every lap or two, with Succeed! capsules every couple of hours, which was enough given the temperature. I wasn’t dehydrated. Sometime later I snagged another Oreo. Same problem. It was the last thing I took from the aid station. The race didn’t lose any money feeding me.

When it’s available at races, I prefer food that’s mushy and smooth: yogurt and pumpkin pie (especially the filling) spring to mind; also cooked foods: hot oatmeal, soups, and pasta are favorites, but last year the grease in the otherwise delicious pizza just killed my stomach. Gels do work if you can handle the usually horrible flavor. I do happen to actually like the PowerGels with extra sodium, but haven’t had any in a while. And soup has to be hot enough to be palatable. Often it’s barely lukewarm.

Even though I basically hate Red Bull—evil-tasting stuff—and would never drink it except during an endurance event, I’ve gotten used to it. It’s easy for me to wolf a half can or can at a time if I just swallow without savoring; and it does pack a wallop. I brought a four-pack of my own, consumed two cans of it a half can at a time at predetermined times, and had plans for the other two later on, if things had turned out a little differently.

Therefore, as far as I can remember, my total race caloric consumption consisted of those two cookies and those two cans of Red Bull. But it’s important to note that I never sensed the need of anything more. I was planning on eating something more substantial a little later. (Do you sense the premonition yet that something didn’t go as planned?)

Another thing I gave attention to during the race was my breathing. Mysteriously, I find that sometimes when I feel short-winded and am suffering, the main reason for that is that I’m simply forgetting to breathe! You might wonder how that’s possible. Isn’t it sort of an automatic and not-optional kind of thing to gasp for air when you need it? Apparently not. At least for me, it’s just a matter of focus, an element of associative thinking, paying attention to what I’m doing. If I’m not feeling right, there’s often a reason for it that can be addressed to make things better.

An important benefit of paying attention to breathing is that it provides a rhythmic backdrop for running. The fuel in our bodies has to be burned for it to be of use. that process begins with oxygen intake, a.k.a. breathing. Not enough oxygen results in slowing down and poor performance, not to mention incredible discomfort. Breathing rhythmically (according to a step count), being sure not only to inhale deeply and diaphragmatically, without forcing it, and also exhaling sufficiently to get rid of the CO2 and make room for more oxygen, is what makes it all happen. Sometimes just being conscious that there’s a problem and fixing it immediately can lead to dramatic relief in just a couple of steps.

Another thing I worked on was my form. I’ll never be on the cover of a running magazine, at least not because of the way I look when I run. (You can stop staggering around the room in shocked disbelief now.) And I have a back that’s never been flexible and that for the last several years has been increasingly affected by arthritis. I’m fine when I’m up and active and exercising, whether running, working in the yard, or just generally moving about, which is probably the best thing I can do for it; but the problem is there and will never go away. And sometimes I can barely get out of bed in the morning. So I tend to slouch when I run.

And I also frequently drag my right foot, seen in the wear patterns on my shoes, which tend to develop silver dollar size holes below my right toes long before the rest of the shoe wears out. Still, I’m not real fussy about shoes, having gone apostate from the shoe religion a long time ago. And while I don’t buy cheap shoes, I do tend to wear them until they are in shreds, and have been known to get 1200 miles out of a pair. As long as shoes provide something between my foot and the surface I’m running on, and as long as they don’t rub me in such a way as to cause blisters (usually not a problem for me once I learned how to prevent them), then issues of cushioning and all the rest don’t matter much to me.

But my body type is such that for me to run like a runner ought to, I have to concentrate, and when I don’t, I immediately fall back into a slouch. So it’s hips forward, permanently curved back as straight as I can get it, look farther than three feet ahead (I often run into people and things—including fences and bushes—because my head is down and I just don’t see them), and swing my arms. Fortunately, my feet don’t splay outward. My stride is about as straight-ahead as can be. Like most runners, I’m a heel striker and have no intention of trying to change that. But nothing I’ve ever been able to do has been able to prevent me from going chuff, chuff, chuff, dragging that right foot.

Again, it’s just a matter of concentration, and on Saturday, as I saw the laps adding up, and being unusually motivated on that day, I was able to focus on it more consistently than usual. Life was good.

One way to run disassociatively is to run with someone else. I’m mostly a loner out there, even in races, not because I’m antisocial, but because most people are running faster than me, and I like to be able to control what I do rather than being driven to one side or the other of what is comfortable for me, going either too fast or too slow—by someone else’s pace. But at NorthCoast on Saturday, I did spend several laps running in the company of Steve Tursi, who was gracious enough to allow me to slow him down a bit while I blathered on and did a brain dump about every little thing I’d been thinking about that day before he finally got tired of me and went off and we parted ways again. And when I was done I found that I was still right about on pace.

Regarding my goal to keep moving the whole race—for most of the first six hours I managed to do that and had no inclination to break for anything. But while talking to Steve I noticed I was starting to develop a hot spot, a harbinger of oncoming blisters. I wore Injinji toe socks with Bag Balm for lubrication—a yucky mess to get on, and painful, too, if you are like me and have trouble bending over in the morning. You have to get those things on just right. Finally, I stopped at my chair, sat down, pulled off my right shoe (a process complicated by gaiters), tugged at the sock, got everything back in place, and took off again. Down time: less than five minutes. I realized immediately I’d made it worse. Hoo boy. I’ve had problems in the past thinking I had a shoe or sock rubbing wrong, only to find that the irritation was coming from an actual blister that had formed. I stopped at a picnic table fifty yards down the path and redid the whole process, forcing myself to be careful. Down time: again less than five minutes. This time I was successful. Whatever was rubbing funny wasn’t any more, never came back, and I had no problem with that or any other area of my feet during or after the race.

So yeah, I did make a stop, but certain minor exceptions are normal and obligatory. My intent was to avoid stopping to rest, upon which I would just stiffen up and would be both unwilling and unable to continue, at least not very well.

Surf’s Up!

If you were at Edgewater Park in Cleveland on September 22, 2012, or followed discussions about the race afterward, then you know what happened to everyone there.

Word had circulated before the race of some heavy rain moving into the area. Being spitting distance from Lake Erie, by about 2:00 p.m., we could see thick black clouds roiling our way, and felt an increase in winds. When it finally hit, it was no ordinary shower or even a downpour, but a mean and hostile squall with some stinging hail thrown in to add injury to insult.

I’ve been caught in substantial downpours twice before at fixed-time races. The first time, at FANS in 2004, was fun. It had been a warm June day, and the evening rain was refreshing. The second was my last time at Across the Years in 2010. I was there for the 72-hour race, but on the verge of getting sick on the first day when a hard rain that began a couple of hours into the race continued to come harder and colder until very late at night. On that occasion I had to quit the race after only seven and a half hours to avoid almost certain personal disaster. (Like pneumonia and death—which would have been a Really Bad Thing—and which happened to someone else at that race once.) It was not how I wanted to end my streak at Across the Years (begun in 1999).

On Saturday I came around to my chair and calculated that I didn’t have time for another whole lap before the rain came, so put on my supposedly waterproof coat (turns out it’s not really) and also a beanie I wear in winter, with my regular running hat stretched over it.

By the time I got around again, there were winds that some people were estimating at 60 miles per hour driving heavy rain and nasty hail into anyone dumb … errr … brave enough to stay out there. At the time I was amused to see five guys suddenly show up with surfboards and wet suits and go enthusiastically plowing out into the lake for an afternoon of fun. Navy Seals out for recreation? The waves were not exactly Hawaii or California type, but I suppose good enough to be effective. God bless ’em. I could never do it.

This all happened just about six hours into the race, so approximately 3:00 p.m. I imagine the details will show in my splits.

And Then

Meanwhile, John Hnat was busy having fun with his bullhorn, recommending that runners take shelter, saying that the heavy rain would continue at least another 45 minutes, but that the race clock would continue to run, and anyone staying out on the course would do so at their own risk. A surprising number of hearty souls did.

I’m no fool. The wind stopped me in my tracks as I came around the final curve to the timing area and ramada, and the hail struck me in the face hard enough to bite. I couldn’t see two feet in front of me. Before long the temperature dropped to about 50, which is not extreme, or even uncomfortable if you’re running and conditions are dry, but if you’re soaked from head to foot, it’s a different matter. I headed into the ramada to enjoy chatting and laughing with other sissies who had come in.

After hanging out for quite a while, the rain was still coming down hard, but the violence had let up a bit. I headed back out to check things out and log at least one more lap, but the break and the wet cold had done their business. I was stiff and could only lumber around at about a 20-minute-per-mile pace, not fast enough to be fun or worth continuing to push it.

Meanwhile, the wind had rampaged through the park. Almost everything that had been put up was blown down. Volunteers were doing their best to cover the computer equipment, which as far as I saw continued to run just fine the whole time without missing a beat. Other volunteers were struggling hopelessly with the aid station—as if anyone was going to be stopping off for dried peanut butter and jelly sandwiches or something in those conditions. They did an admirable job of keeping things going. One volunteer poked his head out the end when runners were coming by and offered to help anyone who needed anything, so at least it was functional, if not exactly five-star restaurant service for the time being.

Out in the tent village on the west side of the course, where almost everyone was set up, it looked like a war zone. All the pseudo-GNC outlets together with almost every shelter I saw had been blown over, and I later heard from some that some tents and other gear had been destroyed completely. Most of the crew people who were helping out the runners who were still out there had apparently fled to vehicles and other places of safety if not comfort, since I didn’t see many people standing around to hand anyone their water bottles filled with miraculously restorative food supplements. (Under the circumstances, a person could have gotten enough to drink by leaning his head back and opening his mouth.)

When I returned from that lap looking like a drowned rat that had washed up on shore, I knew I was done for the day. A lot of people stayed and toughed it out. I later learned that they all endured several more periods of intense rain during the night and that the temperature bottomed out in the mid forties.

So I told Dan Horvath I was bailing out. I detached and gave him my ankle chip, and he ran off to get me something. When he returned he was carrying the biggest “finishers” medal I now have in my collection, which looks surprisingly like a Harley-Davidson logo. “I get a medal for this?” I asked in bemused puzzlement, reflecting on the fact that I’d gone only half of a 12-hour race and was still feeling plenty strong and energetic, if a bit bound up. Oh yeah, there are no DNFs in fixed-time racing. I knew that. Dan got a serious look on his face, shook my hand, and gave me the standard congratulatory speech as if it were like the real awards ceremony, and people were gathered around and applauding my effort. We both had a good laugh about it.

I’ll take it. It’s going in my bling box. Oh yeah, my final distance was about 27.07 miles. And I believe that I was on pace to get close to 45 miles if the conditions had held. I would have been ecstatic with that number.

Of course, it’s one thing to say wanna-woulda-coulda-shoulda-mighta, but I didn’t actually run the second six hours, and most of the Bad Stuff that happens to ultrarunners happens in the later hours, so who knows what might have happened?

So was I upset about my race? Not at all. Yes, I wish it had been nice enough weather to allow me to pursue my original goal as planned. But it wasn’t, and it was absolutely nobody’s fault. Meanwhile, I’d had what was for me an excellent 6-hour run, which I will consider a training run, since I’ll be running the Columbus half-marathon on October 21.

And So

My next feat would be to get out of there. As I stood looking for a break to dash out and retrieve my gear, I had an encounter with an old man who I naturally assumed was there in some capacity in connection with the race, because everyone was, and besides, why else would anyone be out in that exact place in that weather on that day? But he told me he was Romanian, age 68 (didn’t look a day over 85), not a runner, but was at one time a fighter (he had very few teeth) and a weight-lifter. Unbelievably, he was standing in the middle of that soaking wet bedlam, having come there expecting to find someone to play chess with. He said he comes there every Saturday afternoon, that he used to be a highly ranked player, but now he plays only five-minute chess, presumably with a little money to sweeten the deal. I guess it didn’t occur to him that he wasn’t in the best place to find a partner on that day. When I told him I play chess, he thought I might want to sit down for a game. Ummm … no thanks, not this time.

Finally, after a stop in the medical tent to let Andy Lovy’s medical students bump me around a little, which felt wonderful, I decided to just head out to my chair and take the consequences. It was only about 150 feet down the path. But it was still raining very heavily at the time. Fortunately, I had no packing to do, having even already zipped all the gym bag pockets up before the storm hit. So I picked up my bag and chair and took the shortest path to my car, dropping two or three things in the parking lot, which was painful to bend over and pick up. I threw it in the trunk, grabbed the hooded sweatshirt out of the back seat and a towel, climbed in, and did the best I could to make myself comfortable before taking off.

Then I called my wife to let her know I wasn’t going to be rolling in at 1:30 a.m. after all. She reported that it was sunny in Columbus. She’d gone to a picnic!