What do authors Stephen King and David Foster Wallace have in common? As authors, other than having been successful, very little. Their work emanates from about as far from opposite sides of the universe as can be.

Their commonality from the perspective of this neologician is that they are two writers about whom I know far more personally than I do of their written works.

David Foster Wallace I wrote about in the flippant pseudo-blog article Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, which I created as filler to initialize this blog. As that piece points out, the book of the post’s title is about Wallace, not by him, and in that regard it is enlightening. To date I still have not actually read anything Wallace wrote, though doing so is high on my gotta-do-RSN list.

Neither have I ever read a single word of any novel or short story by Stephen King, although I have seen at least two movies made from his work — The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile — and greatly liked them both.

One reason I’ve never read any King is that for the most part his subject matter does not appeal to me. I have zero interest in horror stories, never have, and never will, other than a couple of well-crafted tales spun by Alfred Hitchcock that can be dispensed with in two hours viewing time. Fantasy, mystery, and science fiction generally leave me cold as well, though I’ve read isolated examples of all that I have found enjoyable. Horror, though, I find particularly objectionable for its blood and violence, so have avoided it. Call me a moralist if you will, but I don’t see anything entertaining in reading about psychotics dismembering other human beings and the like, even though I know there are people in this world who actually do such things.

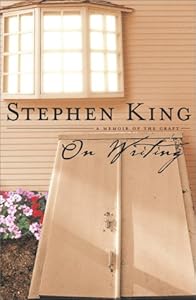

However, this morning I finished reading Stephen King’s non-fiction book On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, in which King discusses, in a surprisingly informal tone, his life history and his substantial experience with writing, presenting just a few useful tips on getting it right for those who would follow in his path.

The first part of the book, titled C.V. (curriculum vitae), he devotes to a series of short vignettes, some less than a page, at first seemingly irrelevant tales from his early life experiences, ending with when he sold his first breakthrough novel, Carrie, written while he and his wife were still Maine-poor, living in a double-wide travel trailer. (I’ve lived there myself and know how that is.) In ways the sequence reminds me of James Joyce’s alter ego Stephen Dedalus, in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, in that it tells in increasingly adult-like fashion of the events that shape the subject from sponge-absorbent child to productive artist.

Having exhausted the subject to the degree King cares to discuss it, he then tells the story of his near-fatal accident on June 19, 1999, when he was hit by a van while out for a walk. Telling this is a sort of self-referential feat of a type I admire, in that King was in process of writing On Writing when the accident happened.

In describing the drunken assailant Bryan Smith with commendable restraint, King tells of Smith’s cretinous decision to leave the scene of the accident while waiting for emergency assistance to arrive in order to buy candy from the corner store for himself and his rottweiler. King adds, “It occurs to me that I have nearly been killed by a character right out of one of my own novels. It’s almost funny.”

Correction. It is funny.

I’ll leave the details of King’s insightful views on writing as an exercise for the reader to discover. You can get the book from most any library or buy it on Amazon. At 288 pages it’s not long, and is an easy read. If you’re not willing to go to the trouble, suffice it to say that you are breaking King’s first principle, and are liable never to become a writer yourself. But that’s okay. Maybe you don’t want to become a writer.

To this little blurb I add one more postscript about David Foster Wallace that I didn’t include in my previous article about him. Wallace goes by his three-part name in writing, but is called only by his first name. For him this is certainly no problem, as no one is likely to assume he prefers to be called Foster. I also go by my three-part name in writing, and have since I was a child, but in my case, there are those who mistakenly assume I prefer to be called David or — curse those who are so presumptuous as to assume the uninvited familiarity — Dave.

I write about Wallace in the present tense, even though he is now dead, because a published writer has managed to accomplish a form of immortality, and will always live as long as his work remains.

And that’s about the only thing I have in common with David Foster Wallace, except that I also lived in central Illinois. But I don’t even play tennis.

Postscript, February 22, 2017 – I just stumbled across this blog post today, having nearly forgotten that I wrote it. Since reading it I have read every one of David Foster’s canonical books, several of them twice (including Infinite Jest), and he has become my favorite late twentieth century author. I’ve also read numerous books by King, some of them very good, some of them only pretty good, others not so good. King in my estimation is not one of the great writers, but a good writer nonetheless.